November 2024

Much of my 2024 has been spent translating into English a book written by Luis Celeiro Alvarez, formerly professor of Sociology and Communications at the University of Santiago de Compostela, and still in retirement an associate professor of Communications Sciences in that university.

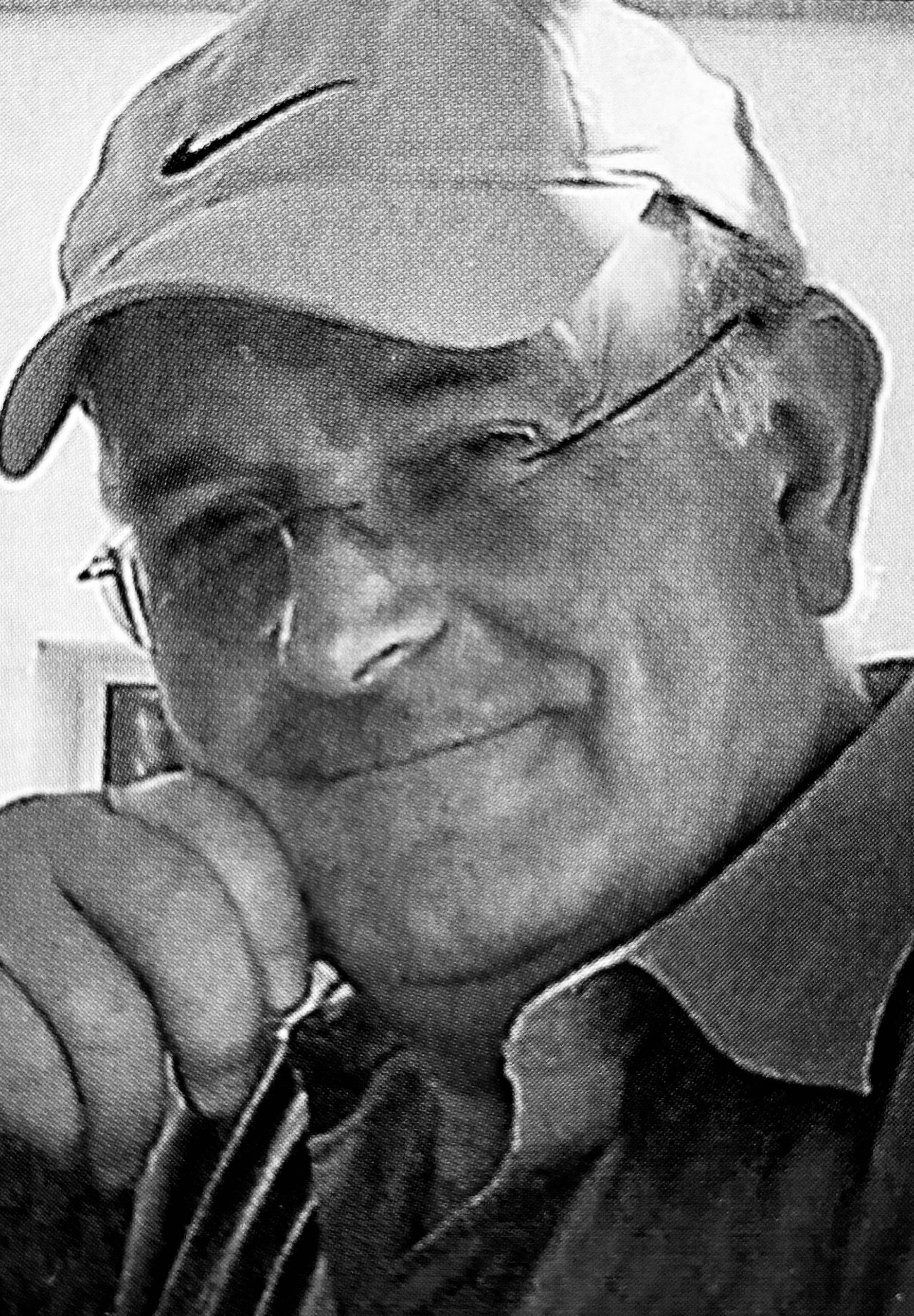

I’ll get to the book in a moment, but first want to mention that from 1990 to 1993, its author also served as personal assistant to Victor Vazquez Portomeñe, then in charge of planning the first ‘Xacobeo’ as the Xunta de Galicia’s Councillor of Culture. Luis is thus one of the few people to have witnessed every stage, from inception to execution, of the modern renaissance of the pilgrimage to Santiago between the 1960s and the present day. He comes from a village near Sarria, and recalls vividly the overgrown and all but forgotten pilgrimage route as it was when he was growing up. The subject of his book - the man who came to be known as ‘the priest of O Cebreiro’ and later, as ‘the man who invented the yellow arrow’ - was still unsung then, but Luis knew him, and like many others, now considers him the pivotal figure in reviving the pilgrimage and the roads to Compostela to the point where the whole phenomenon aroused the interest of politicians and economists in the run-up to the 1993 Holy Year.

This is where Luis’s path and mine cross, because that pivotal figure was Fr. Elias Valiña Sampedro, whom I met when I walked to Santiago in 1986, whom I came to know well and whose last guidebook to the Camino I translated into English. There is a pleasing symmetry in having translated Luis’s own book about Elias Valiña into English in time for the 35th anniversary of its subject’s death on 11 December 1989. ‘Pilgrim Spirit: Elias Valiña and the Revival of the Camino, 1959-1989’ will be formally launched at the Museum of the Pilgrimages in Santiago de Compostela on 12 December. On the evening of the 11th there will be a concert of sacred and pilgrim music in the church of Santiago ‘A Nova’ in Lugo, and on the 14th, an all-day gathering in O Cebreiro, in the church where Elias Valiña is buried and the village he saved from ruin.

Fr. Elias Valiña Sampedro

This will be an occasion that invites friends from the earliest associations of ‘Amigos del Camino’, local people, fellow pilgrims and members of his family to share personal testimonies and anecdotes. Luis Celeiro will act as moderator of what promises to be a moving and memorable tribute.