December 2023

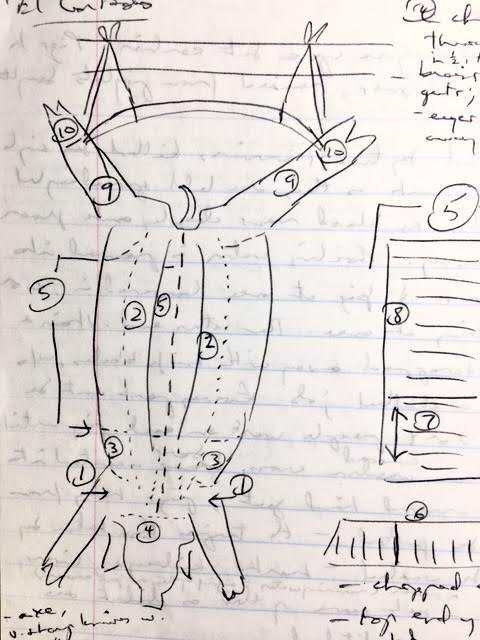

A sketch made at the only matanza I ever attended.

It happens less often than it used to, given the depopulation of rural Spain in the past few decades, but it’s still a tradition that brings families and neighbours together in December when it’s cold enough and there are hands available to do the work. I’m referring to the traditional family matanza, or hog slaughtering, from which emerge the pork products so integral to Spanish cuisine. Nowhere is it more truly said than here in rural Galicia that ‘people eat every part of the pig except the squeak’. The amount of nourishment that can be obtained from even one pig is astonishing – and a matanza usually involves at least two and sometimes as many as six. Turning this into a year’s worth of food is an immense amount of work. A matanza is usually spread over three days, but it’s also a communal, social and reciprocal occasion. In a village, or an extended family, everyone lends a hand, knowing that when they hold their matanza, they can count on help too.

Nowadays, a skilled man arrives on the morning of the first day to kill the pigs. His time has been booked and paid for months in advance, so he does the job quickly and departs. Others then scorch, scald and shave the pig’s body meticulously before washing it with a pressure hose. Once the carcass is hung up and opened, the viscera are removed and the body left to chill overnight. The parts that will become casings for embutidos, or cured meat products, are taken to the nearest source of running water to be washed. Evening brings everyone to the table for a supper of liver stewed with onions, brandy, breadcrumbs and herbs, followed by filloas, or crepes made with some of the blood collected that morning.

The second day is the most intense, and begins with the dismembering of the carcasses. Practiced hands wielding long knives separate the back legs from each body as jamones (hams) and the front pair as lacones, or shoulders. Then, in stages, the layers of fat are removed from the carcass and the quality cuts set aside for hanging, freezing, or preservation in salt. Some chops are fried up then and there, for everyone to try with the year’s new wine. Nothing is wasted, though children and dogs hang about in the hope that some tidbit may come their way.

Traditionally, men do the jobs requiring physical strength, but the ingenious preparation of extremities, heads and innards on the second and third days relies mainly on women, as does the creation of the mixture of meat scraps, fat, salt, garlic, herbs and finely ground roast red pepper (pimenton), that is kneaded together for stuffings. Dishes that employ this include botillo (stomach or large intestine, filled with short ribs and the seasoned meat mixture), chorizos (lengths of small intestine into which the seasoned mixture is fed, then tied off with string in 15-cm. lengths), and morcilla (blood sausage). All of these will be cured for several weeks, sometimes by being smoked. Like them, items such as manitas (trotters), codos (hocks), orejas (ears), and rabo (tail) are winter mainstays. The second day ends with a festive meal featuring zorza (fried, highly-seasoned pieces of lomo, or pork shoulder), with potatoes, chestnuts, corn bread and greens in the form of caldo, or broth. It remains on the third day to ensure that hams are well buried in salt, that chorizos are hung where there’s good circulation, and that implements are clean and properly stored for the following year. Everyone is weary, but larders are full.